Over lunch this past week an interesting hypothetical was posed. Suppose you were offered one of the following, which would you choose:

- One million dollars in some initial combination of your choosing between stocks and bonds (fully-indexed, total market coverage), or

- One million dollars in some initial combination of your choosing between Bitcoin and cash (U.S. dollars).

You will be forced to lock it in for 10 years with no changes to it or any ability to borrow against it. After the 10-year period is up, it is yours free and clear (no taxes either at that point).

Without too much thinking or much hesitation, I chose Bitcoin and cash in a 50/50 combination. My wiser colleagues said with as much or more conviction stocks and bonds--I don't recall their combinations if they stated them. Since I am the investment guy, this raised eyebrows. Maybe I'm just also the gambler. To be sure I caveated my decision with the disclaimer that I might change my mind (my guess was low conviction). To be fair the others did similarly but with perhaps a bit less hesitation (somewhat higher conviction).

In general I would assume that all four of us in this conversation are of very similar financial standing adjusted for our ages (there is about a 30-year spread from youngest to oldest). There is not a right or wrong answer on this question--at least not without a lot more information about each chooser including several underlying assumptions (risk tolerance, liquidity needs, expectations about each person's future goals and paths of life, etc.). I don't wish to get into speculation about that here nor try to evaluate the soundness of any starting position.

What I am interested in is exploring further how we might frame such a tradeoff. One additional outcome from this exercise is thinking about what assumptions one would make about critical variables and the implications of those assumptions.

Some people would very appropriately, for themselves, choose an allocation of 100% cash. We could argue about that, but again only by digging deeper into their goals and risk tolerance among other things. "Hey, I'll take free money and I want to know it will be basically there for me at the end of the rainbow (inflation be dammed!)." That is potentially a sensible position, but we could write a book (many books have been written) about what extreme conditions must be in place for that to be rational. Geez, I better stop now or that will be this post . . .

So let's just assume we are debating only the question of which outcome has the best highest expected value after 10 years. I strike "best" because that implies more than just the math problem I want to explore.

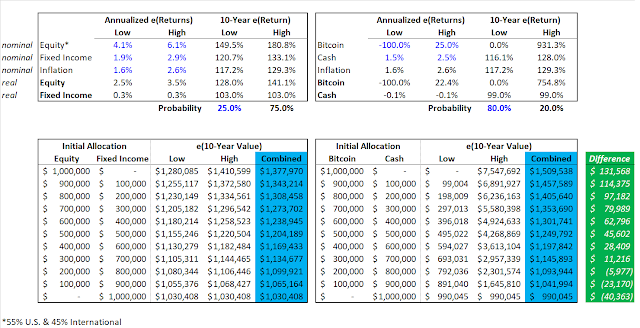

We need just a few inputs:

- expected returns of stocks, bonds, Bitcoin, and cash (I am assuming we can get some yield on cash rather than thinking of it as money under the mattress.)

- expected inflation (We are going to look at values in real terms so we don't let the cash option appear better than it actually is--a likely net loser to inflation.)

- probability of various outcomes (Using a range of expected returns we need to know how likely we think those are. The range is really only important for Bitcoin given its unknown future.)

I am going to use Vanguard's capital market assumptions (CMA) for expected returns of stocks, bonds, and cash as well as inflation. To make these always updating predictions evergreen in this post and because these are publicly available information as linked above, I will also post a picture of these below. Please do see Vanguard's website for more information including appropriate disclaimers.

I am going to totally make up the expected returns for Bitcoin because 1) my guess is as good as yours and 2) the devil is in the probability and the relative outcome versus the others--my accuracy is nearly immaterial if I am in the ballpark.

Before you dismiss any of this upon glancing at the inflation prediction (range 1.6% - 2.6%), understand that these are 10-year predictions. I hope they are right given what this implies going forward given currently very high inflation rates, but it can easily be the case even with some persistence of current inflation (8% for a year (not that bad yet) plus 5% for a year plus 8 years at 1.6% would land us at the high range).

Note that I am looking at true total market coverage in stocks (U.S. and all international), thus I will combine the growth rates below in the proportion 55/45 U.S./Int'l. Note also that I am only using U.S. bonds in the model. I generally like some international bonds, but I will make this limiting assumption. Regardless, U.S. versus Int'l bond returns are pretty close as you can see in the details below and at the link.

Enough of that already, let's model this thing.

Here is version 1:

But just before that, let me explain why I don't think we need to worry about the mixing and matching between individual high and low estimates (e.g., stocks grow at 6.1% while bonds only grow at 1.9% or stocks and bonds are high but Bitcoin and cash are low, etc.). Assets tend to be positively correlated over longer and longer timeframes. Even though stocks and bonds enjoy some degree of poor correlation, these fade away over time as what is good for stocks (a productive, growing economy) is also good for bonds. Likewise, a world that has Bitcoin doing well probably has stocks doing well, and a world where inflation is low, stock and bond returns are also probably low. Regardless, the heart of the debate isn't going to be impacted by these details.

Here is version 2:

Ouch! Even though I made the low-high range for stocks and bonds 50/50, the move to make low to high outcomes 95/5 for Bitcoin destroys that option. But if that is really more like the future likelihood of the outcome range for Bitcoin, perhaps stronger return possibilities on the high end are as well. So . . .

Here is version 3:

I greatly increased the growth rate for Bitcoin using 38.6% annual growth. This isn't a randomly chosen number. This would correspond to a Bitcoin price of approximately $1,000,000, which some roughly project as a possible destination (who knows?). Regardless, stocks and bonds still look better. So let's do just two more for the sake of good order . . .

Here is version 4:

Finally, here is version 5:

So, allowing for a Bitcoin future in any future (low end is 10% annual decline in value) gives us a fairly strong case for my gamble on some combination of Bitcoin and cash.

Having gone through this process would I now change my mind? I will stick with 50/50 Bitcoin and cash. But that strongly suggests a question: how can I justify that choice given that I don't have an existing portfolio that looks anything like that. I am personally overwhelmingly "boring" with an almost all-stock portfolio with just a bit of crypto sprinkled in.

At the risk of a slight digression into the post I keep promising this will not be, allow me to defend my rationality. This hypothetical is a forced gamble. My retirement investments are different in that regard. Those I can and do change periodically including both allocation as well as contribution. I get to guide those and adjust them. The hypothetical gift invested is a Ron Popeil "set it and forget it". Part of why I cannot invest more in Bitcoin (aside from it wisely not being a 401(k) option (looking right at you, Fidelity)) is that I likely cannot tolerate the variance. If I can get in and get out of it, I am as more likely to make the wrong in/out moves as the right ones. And that is before the tax-drag effect.

Besides that, my investment reality is the retirement assets I actually do have. This hypothetical is a lottery ticket idea. If I win the lottery, my reality materially would change. I could afford more and different risk. In this sense and surprisingly, if the hypothetical was $10,000 in stocks and bonds versus Bitcoin and cash, the rational decision for me might have been stocks and bonds! Whereas the typical person would say, "that is too little to worry about the risk, let it ride!", I would counter, "I can't afford to take the the riskiness of Bitcoin at that magnitude ($10,000)." Along this one dimension, I would be right.

I want exposure to big upsides. Unfortunately, these are difficult to find and doubly difficult to stick with. In a sense this thought experiment has revealed some of my own limitations on putting my money where my mind and heart and mouth are.

-----