I have just returned from a family vacation in Cape Cod which began with a brief, 3-day stay in New York City. We flew into NYC and then rented a car for the drive to the cape. Below I note a few observations from the trip. These are just trivia compared to the wonderful time we had in both locations. Chatham, our regular destination in Cape Cod, again proved to be a splendid escape.

- My Lyft driver said as we were crossing the Queensboro Bridge, “the greatest city in the world without a doubt.” He is much better travelled/lived than me—born in Nigeria; lived in Dubai, Shanghai, LA, somewhere in Europe as well as several other worldly locales I don’t recall specifically. Who am I to argue? NYC is indeed world class. It’s ability to overcome so much poor and excessive governance is a tribute to its greatness.

- NYC is vibrantly crowded—in a very good way. This was refreshing to see as I feared the city might have lost this by an order of magnitude.

- Outdoor dining is generally well placed and seemingly here to stay. The outdoor market near Times Square on Saturday was new to me and a treat to walk through.

- New condo high rises are incredible. These so-called "pencil towers" don't inspire me the way other skyscrapers do, but maybe I'm too caught up in how structurally unsound they appear, which is intended as a feature rather than a bug. Just to me they look like how a child might sketch a cityscape lazily drawing as many tall buildings as possible.

- Residence Inn Central Park (54th & Broadway) is recommended. Laundry options and convenient location along with great room and views—pics below.

- Office space use looks still near empty by my anecdotal evidence. These pictures were taken from my room. Of the many elaborate office floors pictured in the neighboring building, only one ever had any occupants other than cleaning crews--cleaning floors that didn't ever have office workers messing them up. The floor with the basketball games and other fun stuff was vacant during the day. Note that the machines were all on 24/7--this should probably count against this firm's ESG rating, LOL.

- Where are the homeless? Michael Shellenberger has a point. Considerably less panhandling total than I encounter in the OKC area with 1/14th the population.

- Crime and safety never seemed an issue on this trip. While I was in relatively high-income places, the popular narrative from the right still seemed false. We walked about 8 miles per day in various areas:

- Times Square (at night!)

- Greater Midtown area

- Central Park to the Upper West Side

- High Line/Chelsea Market to Little Italy/Chinatown

- I left my family shopping at Rockefeller Center to go pick up the rental car planning on them walking the half mile back by themselves without a second thought. I would have hesitated to do this in downtown OKC. Their journey was uneventful.

- Memories come serendipitously. On our first night we were caught in a downpour in Times Square. While some of us had rain jackets, we were ill prepared. We stopped into a CVS to buy a couple umbrellas. Still our shoes and socks were quite soaked. This was very much like Boston years ago. No one would plan to get caught in the rain like this, and it would undoubtedly be one of those wouldn't-do-that-again moments. Yet, how can we reconcile that with it also being a wouldn't-trade-that-away moment? We don't get to choose our moments, but we do get to choose how we feel about them and how we take them on. (NB: I still plan on making good on this from the prior post: "The imaginative story we concocted on the train-ride back will be the inspiration for a future post.")

- Masking is relatively high. ~20-25% of people still mask and those that do do it constantly—inside, outside, between bites. These are the people suffering long COVID. One young man walking down a busy, curvy street in Central Park choose to avoid passing our group in a tunnel under a bridge by walking down the middle of the street. He crossed between speeding cars, walked down the double-yellow line in the shadows of the tunnel holding his Macbook up high as cars whizzed by, and crossed back behind our trail. He seemed to stride with some pride in this moment of horribly bad risk analysis.

- Book stores are the last holdout on required masks (aside from public transportation where it actually isn’t enforced). Stores in both Greenwich Village, NY and Chatham, Cape Cod strictly adhered to the antiquated ritual.

- Cape Cod is resilient as well. Hard to tell a difference from my last trip in 2019.

- Mask use is lower here than NYC. Maybe 15% tops. Very few outside.

- Police are used for traffic directing around construction. This is something I noticed in Boston a few months back. In Cape Cod four or more police can be found just standing around pointing for cars to drive or wait as construction workers actually work. Definitely a union giveaway—great to see all the crimes have been solved in Massachusetts.

- People were quite friendly almost everywhere in both places. The northeastern USA's reputation of unfriendliness is again proven quite unwarranted. Distant and reserved, yes. Hostile or gruff, not so much.

- Rideshare the business model as experienced via Lyft seems strong and competitive. Uber was just a tad more expensive on each prospective trip but highly available as well.

- Prices are high but a competitive market helps. Cocktails were basically the same price at comparable bars to what I see back home. Food was more expensive but an order of magnitude better when considering availability times quality. As for prices, it is hard to know how much is inflation versus big market, if only I had a restaurant journal… oh wait, I do.

- Let's begin by comparing Nom Wah Tea Parlor between my visit in June 2018 and current prices in June 2022. Recreating the order from the prior trip (beer, tea, 3x buns, 2x dumplings, roll, rice, and noodles) yields a total bill of about $69 pre tax & tip. My total bill with tax & tip in 2018 was $68.72. Assuming the tax rate is the same and I tipped the same rate, the total bill difference goes from $68.72 to about $89--about a 30% increase. In comparison NYC-area restaurant prices in general as measured by CPI over this time span are up about 18%. A similar order made at my local option, Mr. Hui, comes to about $93--more expensive and lower quality (sorry, Mr. Hui). My bet is Nom Wah got discovered between then and now, and its prices are reflecting as much. Hence, the 30% increase is a combination of general food inflation and something specific to that restaurant.*

- One more comparison: The Chatham Squire, which I always hit multiple times per trip. In June 2019 I was there with extended family. Our total bill was $202.05 for which we enjoyed (well, let's just say quite a few drinks) and cioppino, mussels and hummus. Recreating the order in June 2022 makes the total about $253--about a 25% increase.*

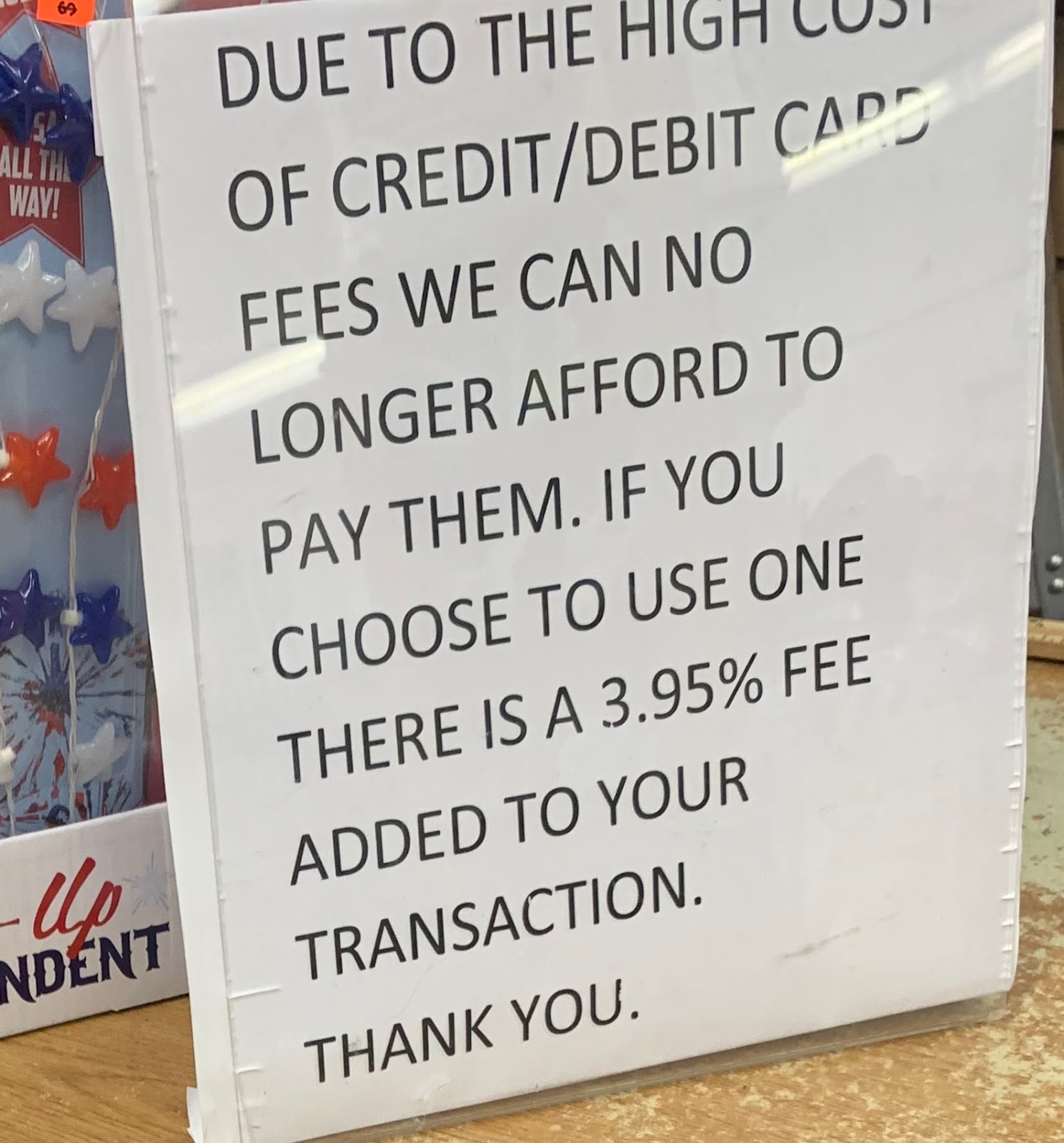

- Pervasively merchants are directly passing along credit card fees in Cape Cod and to a lesser extent NYC. This has got to be an intermediate solution to a standard menu-price inflation problem. Seems slightly bullish for crypto while obviously creating a distortionary arbitrage for the cash-based consumers.

- Employee scarcity didn't seem as bad in Cape Cod as NYC or back home, but the effects were still in evidence. Restricted hours of operation seemed the most obvious sign. Restaurants were otherwise packed.

The trip was delightful as I could have easily enjoyed double the time in each location. Cape Cod is very relaxing especially the way we do it. If you feel rushed there, you're doing it wrong. Enjoy a few pictures.

*Take these comparisons with a grain of salt since you really cannot tease out anything from an N=1 sample.