Bold title, I know. Yet while there may be some hyperbole in it, we do face a situation in equity markets quite unlike anything we've seen since the dot-com tech bubble era.

[Disclaimer: This is not investment advice because I don't know you. I am not analyzing your situation, your appropriateness or suitability for equity or any other investment idea, your goals, or your risk tolerance. This is an attempt to explain what I believe to be the valuation existent in the market today. Read at your own risk.]

I. The Trade of The Decade

Typically with tolerable variation equities are "cheap" or "expensive" at the same time. The Great Recession was a period where equities went on sale, so to speak, for those willing and able to bear the risk. You didn't have to be brilliant; you just had to be brave. Buying and holding throughout the deepest points of the downturn (roughly Oct 2008 - Mar 2009) was a rewarding investment. Make no mistake it was not easy to do this as for years after the market bottomed it still never felt quite safe, but that is what investors generally and equity investors specifically get rewarded for--buying when no one wants to.

At least they should be rewarded for that. And the expected reward is the "risk premium"--the expected return over and above the return for a risk-free investment. Think of it simply as the premium you should expect to earn for bearing the risk. Every investment has one. Sometimes it is relatively high like for stocks in the early 2010s. Sometimes it is relatively low like for stocks in the late 1990s. That "relative" measure could be in relation to its own history alone, the position of that asset class compared to other asset classes, or both. Current market risk premiums are the foundation behind my hypothesis that a big opportunity/challenge is in front of equity investors today.

The "trade of the decade" I allude to is a relative trade. Unlike so many highly-touted trades in history, this one is fairly simple. I wish to briefly outline it without effectively proving it so as to get to the true purpose of this post: a hypothesized reason for the opportunity to exist in the first place. After all, I am a strong supporter of semi-strong efficient markets theory (EMH).

First, some assumptions:

- Markets are generally efficiently priced. This means all important known information is thoroughly and quickly incorporated into market prices. Therefore, an investor should not expect to be able to outperform the market.

- Risk tolerance (degree of risk aversion) among investors and risk outlook (the economic picture going forward) determine risk premia. The world looked very scary in March 2020 and investors' general appetites for risk were substantially lower than usual.

- Risk premiums today are generally low across all asset classes. A couple of ways to say this in everyday language are: equity returns going forward (next ten years) will be lower than what we have enjoyed historically especially in the last 11 years and interest rates look to be lower for longer (lower than historically and for longer than typically has been the case). Caveat: risk premiums can be low and returns look high and vice versa. I am being a bit casual with how I equate risk premiums and future returns as compared to history, but I believe the underlying point holds.

Here is the problem, opportunity, and challenge all rolled up into one. Today certain portions of the stock market look fairly expensive (high valuation) while other parts look fairly attractive (low valuation). To be more concrete about it the high/low valuations are in comparison to those specific equity subclasses' own history. However, adding to the puzzle the risk premia for those asset classes look typical for the expensive group while they likely are desirable for the attractive group.

Even a sloppy reader at this point is growing quite frustrated by the fact that I haven't identified which groups of stocks I put into the expensive and attractive categories. That is intentional as I don't want that to be the takeaway from this post, but I will now relieve that frustration as long as you know I am NOT effectively proving my case. Take this too as assumption.

From the perspective of valuation, large-cap stocks in the U.S. (especially growth-style stocks) are expensive compared to their own history. Small-cap stocks in the U.S. (especially value-style stocks) are cheap compared to their own history. International stocks (especially value-style stocks) are also cheap compared to their own history. One way to measure valuation is to look at the current market price compared to the earnings, the P/E ratio. The higher the ratio all else equal the more expensive the stock.

One of the best ways to see this is to look at long-term analyses of real (inflation-adjusted) price/earnings ratios. The most famous of these is Shiller's CAPE (cyclically-adjusted PE) for the S&P 500 index.

We can then do very similar analysis on various other indices considering important subclasses to see how they compare to the S&P 500 (large-cap U.S. stocks). This analysis [summarized in the table below] is where we see these key differences. Namely, that the riskier areas of the stock market (value-style companies, smaller sized companies, international companies, et al.) look relatively inexpensive.

Risk premiums* [analysis and results not shown] both echo some of the valuation analysis as well as tell a bit of a different story. The risk premium for large U.S. stocks is near the median of where it has been over the last 15 or so years meaning that adjusted for risk these stocks look appropriately priced. The risk premium for small U.S. stocks is far above its own historical median meaning adjusted for risk these stocks look very low priced. To a lesser degree the same low price depiction can be ascribed to international value stocks. The risk premium for international growth stocks is more similar to large U.S. stocks (i.e., it is around its historic median). So we have a general range of stocks from those that look appropriately priced (safer stocks like large companies and growth-style companies) to those that still look attractively priced (riskier categories mentioned before).

The risk premium story is not as sanguine for large U.S. stocks as it may appear. Despite my assumption above that interest rates will remain low for a long time, they don't have to. And they can rise meaningfully above current levels and still be historically low. If they do rise, that will have a big impact on stock valuations. Large growth stocks in particular look very sensitive to this risk as their cash flows come far into the future. A rising interest rate means a rising discount rate applied to those cash flows, which reduces the current value of the stock.

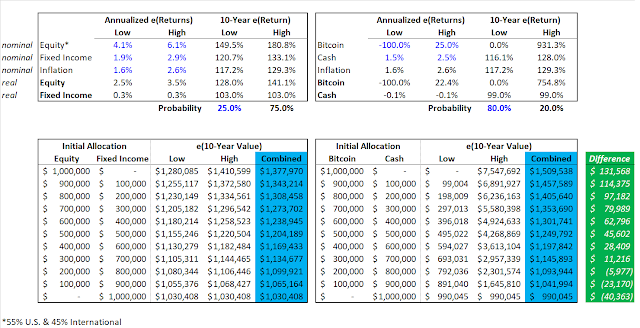

The trade of the decade is to fade away from large U.S. stocks and increase exposure to small U.S. stocks (especially value) and international stocks (especially value). The most acute version of this is for large growth versus small value stocks in the U.S. Specifically we could identify indices like the Russell Top 200® Growth Index and compare it to indices like the Russell 2000® Value Index. The reason I call it the trade of the decade is because my more in-depth analysis focuses on 10-year expected returns and risk pricing as well as the fact that it might take a decade to fully play out. The reason you should heed caution before engaging in this trade is (1) this risk might not be for you (it indeed comes with risk not specified in this post) and (2) this is not an endorsement of reducing diversification (I still advocate exposure to large-growth stocks, etc.).

II. The Crowding Theory

IF I am correct about the different relative risk-adjusted valuations for various equity subclasses such as large growth stocks versus small value stocks, interesting questions emerge. How did this come to be? What explains it consistent with EMH?

I believe two crowding effects have brought this about. Flight to safety is the first crowding effect. Sophisticated money avoiding public equities is second.

Recall my assumption that risk premia are determined by the general level of risk aversion among investors and the market's risk outlook. The tidal wave of the pandemic that unfolded gradually then suddenly from mid-January 2020 through to the market bottom of late March 2020 was a massive reevaluation of risk that triggered an extreme flight to safety. Note that it was not the entirety of the valuation dispersion between various groups of stocks. For some time now growth has been outperforming value, large has been outperforming small, and U.S. has been outperforming international. For U.S. equities the market's reaction to the pandemic was in fact the dominant portion of the differences we see today.

From Vanguard:

Difference in annualized total returns over rolling five-year periods

|

| Source: https://advisors.vanguard.com/insights/article/growthvsvaluewillthetideschange |

As the risks and worry of the pandemic grew, investors sought refuge in the safest of assets, U.S. Treasury securities. This lowered interest rates to nearly zero across the yield curve. They also derisked in other ways. For those who wanted continued equity exposer, they flocked to the safest equities in the world, large U.S. growth companies. The now much lower interest rate conditions worked in tandem to make these equities more and more attractive. The riskier aspects of the market suffered as investors tended to rotate away from them and into safety.

So that is how risk premiums for various stocks got so extremely different, but why didn't sophisticated investors step in to absorb the difference? After all, they are supposed to have extremely long (infinite?) time horizons and not be subject to wild swings in risk.

Sophisticated investors is a bit pejorative on my part. Here I am talking about the so-called "smart money" of institutional investors like endowments and pension funds. They like to think of themselves as cunning lions, but they bunch together like scared, vulnerable sheep. Theoretically, they should be a counterbalance to short-horizon investors who are theoretically much more sensitive to changes in risk appetite and risk conditions.

For example, a person close to or recently entering retirement should be invested positionally to withstand the risk of market volatility. The same can be said of any investor--they should be so positioned. Yet often times they are not. And even more often they are liable to overreact to bad news leading them to drastically alter their investment positioning as an attempt to predict the future. However, I do not think this is a big effect. It is a behavioral story that isn't necessarily as irrational as it seems--extreme events like the Great Recession and COVID pandemic give us insights into our attitudes on risk tolerance not apparent before.

At the same time the sophisticated investors themselves are subject to the same types of risk tolerance reevaluation. Rather, to be a counter-balance they need to be in the market. The reason why the “smart money” hasn’t absorbed all the excess risk premium in riskier aspects of the market already is because endowments and pensions have trended far from traditional public markets. Endowments have on average reduced their public market equity exposures by 50% in the past 50 years going from about 60% to less than 30%. They are crowding away from public equities making them unavailable to provide a counterweight.

To be sure riskier assets have done well in the past few months--small-cap U.S. stocks were up 35% for the three months ending in January 2021. The primary catalyst were vaccine developments in November. Add to that improvement in our understanding of the true risks of the pandemic as well as rapidly improving economic fundamentals. Even still, risk premiums in risky assets (value, small cap, international stocks) are at elevated levels compared to their own history as well as their safer equity counterparts.

As risk aversion gradually (and perhaps in sudden bursts) returns to normal levels and as the risk outlook continues to improve, my hypothesis is that those assets with outsized risk premiums will perform relatively well (high confidence) and absolutely well (moderate confidence).

Incidentally while this bodes well for public risk assets, it likely portends poorly for alternatives (private equity, venture capital, hedge funds, et al.). That is a crowded space with not much low-hanging fruit, and what is there is very expensive to be had.

*The reason I deliberately gloss over the risk premium results is the model I am referring to is proprietary, but more importantly the calculation of risk premia is art and science. Laden with assumptions, it can be very much argued over in fine detail. However, I believe the depiction above is well grounded and firmly supported by a wide range of reasonable underlying assumptions. For more on this topic see Research Affiliates work among many others.