- Take in lots of diverse information.

- Be willing to change your mind.

- Gracefully stand up for what you believe in.

Sunday, May 22, 2022

Advice to a Recent Graduate (and everyone else too)

As it is currently graduation season, I was recently asked on-the-spot to provide some advice to a recent graduate. Below is what I came up with. I think it is decent advice for all of us at all stages of life's graduations.

WWCF: War of the Future

Which will come first?

Intentional detonation of a nuclear weapon as an act of war

or

A battle with robots fighting robots as the dominant form of combat

Terms:

The basic terms are fairly straightforward in the first case--a nuke blows up on purpose designed to hurt targeted victims. But I guess there could be some ambiguity like if a bomb detonation is attempted but somehow fails or is thwarted or if it melts down rather than properly explodes. In the interest of specificity I will stipulate that the device must be truly an intentional nuclear explosion.

In the second case there would seem to be a lot of room for interpretation. Let us stipulate that it would need to be a significant engagement with at least a potentially meaningful affect on a larger conflict if not be the entire war by itself. This must be a major conflict in terms of world events. It must involve at least one nation state with the opponent being at least a major aggressor (significant terrorist group, etc. if not a state-level actor itself). To be robot-on-robot it must mean that humans cannot be directly targeted in the robot versus robot fighting--collateral damage notwithstanding as well as other human involvement/risk as a secondary part of the combat. I will allow that the devices doing the fighting can be "dumb" devices like drones fully controlled by humans remotely, but extra credit to the degree these are autonomous entities.

Discussion:

Tyler Cowen has been thinking a lot about nuclear war and nuclear device detonation recently including before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. His latest Bloomberg piece discusses just how thinkable the "unthinkable" has become. This is a bigger part of a much needed rethinking of MAD.

Tyler's partner at Marginal Revolution, Alex Tabarrok, is in the game contributing this overview of the related probabilities.

Thankfully, Max Roser has done the math for us. Relatedly, he argues that "reducing the risk of nuclear war should be a key concern of our generation". Before we get too excited about a white-flash end to civilization, consider as gentle pushback this piece arguing that nuclear weapons are likely not as destructive as we commonly believe--make no mistake, they are still really bad.*

If Roser is roughly correct, then within a decade we are at a 10% chance of nuclear war. I am not sure if his "nuclear war" would be a equal to or a different level of what would qualify in this WWCF. Suppose it is a higher threshold. Let's make the probability of nuclear weapon use as defined here slightly higher each year such that there is a 20% chance within 10 years (basically equal to his 2% annual risk curve). This gives us a baseline for comparison.

Turning to Rock 'Em Sock 'Em Robots it is not as farfetched as I think most people believe. In fact we may be quite close to it as defensive weapons like Israel's Iron Dome prepare to confront adversaries like drones and Saudi Arabia battles against drone counter attacks from Yemen. As Noah Smith writes, "the future of war is bizarre and terrifying".

It does sound terrifying in one reading, but in another there is a glimmer of hope. A proxy war using robots to settle disputes could be vastly better than any conflict humanity as known before. Imagine a world where the idea that a human would be actually physically harmed from combat was unthinkable. This is not too many steps away from professional armies, rules of engagement, and norms, laws, and treaties against harming civilians, et al.**

Back to the issue at hand, once we consider that dumb, remotely driven/released weapons might soon be battling smart, sophisticated devices with either of these being on defense from the other, we quickly relax how hard it is to foresee it all happening. The hardest hurdle might only be if the conflict big enough to qualify.

My Prediction:

I think nuclear risk is a lumpy, non-normal risk that follows a random walk (i.e., it can all of a sudden get a lot more likely but that likelihood can get absorbed away if conditions improve). It is not as linear and cumulative as Roser suggests. At the same time play the game long enough and anything will happen.

Robot battles seem more like a cumulative progression, an inevitability. We almost cannot escape it eventually happening and probably soon. So, this comes down to how likely a nuclear pop is in the very near term as it tries to out race the tortoise of robot warfare. Just like in the fable, the turtle is going to win.***

I'll put it at 75% confidence that we see this one resolved robot fights robot.

*Of course other future potential weapons that are not nuclear can be extremely scary too--"Rods from God" doesn't just sound very ominous; it truly is.

**Then again, maybe not:

As a result, conflicts involving AI complements are likely to unfold very differently than visions of AI substitution would suggest. Rather than rapid robotic wars and decisive shifts in military power, AI-enabled conflict will likely involve significant uncertainty, organizational friction, and chronic controversy. Greater military reliance on AI will therefore make the human element in war even more important, not less.

***I know they aren't the same thing!

P.S. When I first conceived of this WWCF, I thought I'd be comparing robot wars to lasers as prolific, dominant weapons. I changed it as laser weaponry seemed to be consistently failing to launch. However, great strides have been made recently in this realm. Perhaps I was too hasty. However, thinking about it more I would guess that robot war will go hand in hand with laser weaponry. The development of one spurs the development of the other such that there isn't much room for a WWCF.

P.P.S. The ultimate tie would be an AI launches a preemptive nuclear strike on a rival nation's AI or other robot weaponry. Let's hope if they do this the battle is on Mars.

Sunday, May 15, 2022

The (False) Law of Conservation of Effort and Reward

Most people seem to think within the framework of a supposed "law of conservation of effort and reward" (LCER) and its corollary "law of conservation of happiness". One might think of these as a spin on the forever-popular and equally incorrect labor theory of value.

The thinking goes that somehow there should always be a linear and somewhat direct trade-off between work/life balance--that is, the effort one puts into something should be proportional to what one gets out, and there should be a trade-off between the chosen path and the "obvious" alternative path that together net out. Tightly zero sum.

People resent the very idea that someone could have it all. The working mother should have delinquent kids who don't love her; the investment banker should long for relaxing weekends and be doomed to an unfulfilling life without meaning.

The problem with these laws is that they conflict starkly with the magical human ability to tap the power of scale and compounding. The dynamics that these forces bring separate man from nature. Animals cannot coordinate nor plan for the future nor command exponential growth in any meaningful sense the way people can.

Therefore, it should not be any surprise that some people and organizations can get more out of less and excel along multiple dimensions. In thinking about jobs, sometimes the grass is actually almost always greener.

Consider how many people look to sports stars and other icons as “great follows” in social media making them big influencers succeeding in a realm outside of their primary area of success. Many adherents to LCER dismiss this as some obviously irrational behavior on the part of those less enlightened than themselves. The truth is these influencers probably are above average in ways that impact both the direct source of their fame (say basketball skills or acting ability) as well as many other areas. IQ becomes more and more important in sports the higher and higher the level. Dumb athletes don't last long at the pro level.

Jeff Bezos would probably be an above average gardener. The reason he doesn't mow lawns and trim bushes isn't because he wouldn't be very good at it. He might in fact be better than the people who do the job for him at his own house(s). If you think he doesn't do those jobs himself because he is rich, you're right for the wrong reasons. The reason he doesn't is because of the very real law of comparative advantage.

At the same time I think that some of what makes amazing people amazing often has a dark side. This might make them a bit eccentric or frustrating or detestable. It varies and is not always the case. This might sound like a contradiction, but I don’t think so. Rather it is part of the complexity and mystery of it all—what distinguishes elites. This is very much in agreement with point #6 here.

Arnold Kling makes related points calling this the "convergence assumption":

What I call the convergence assumption is the assumption that everyone is fundamentally the same, so that it is more natural to expect people to develop the same skills and adopt the same values than for divergence to persist.

...

We are not all the same. This makes moral issues very complicated. When we acknowledge genetic and cultural differences, what is the meaning of equality? When should we suppress differences and when should we accommodate them?

I think that the great appeal of the convergence assumption is that it allows us to avoid the challenge and complexity posed by these problems. But avoiding complexity is not a good approach if the complexity is an important characteristic of the environment.

Exceptional people are generally and not just specifically exceptional. How this maps onto agreement with you will vary along dimensions of morality as well as taste among others. Those differences are not tradeoffs they are making such that in some cosmic justice sense you and they are on equal footing when all is balanced out.

Saturday, May 14, 2022

Knowing Your Business Means Knowing Your Costs

[Sister post to The Accountants Can't Make You Rich; consider this the counterpoint to that post.]

To understand your business, you have to understand your costs--at a total, average, and incremental level. Many small businesses that would otherwise be successful fail for lack of this understanding. Think of a restaurant that clearly has a sufficient level of customers but that nonetheless closes its doors permanently.

To be sure, many businesses manage to stay alive and in some cases thrive despite anyone understanding their fundamentals, but these examples are rare and fleeting. More often what seems to be operators flying blind are actually people with some combination of magnificent instincts and great muscle memory honed by years at the treacherous helm.

Truly understanding the underlying drivers of costs unlocks the ability to guide all manner of vital decisions: what to make and how much, how to shrink when necessary, where you can discount and where you cannot, where to expand operations and what to expect from growth, etc.

Cost per the relevant unit is as essential as it is boring to all but a few of us, an elite group who relish mastering the concept. The good news is there are only two difficult parts to that equation, but the bad news is the same.

Cost is an elusive concept. Defining cost properly is where economics meets accounting. Here we must understand variable versus fixed costs, marginal versus average versus total costs, the thresholds of cost expansion/contraction (At what point of production must we build an entirely new production plant? If we shutdown a production line, how are costs affected?), cost drivers and probable variances, etc.

Defining the unit(s) that is relevant is the art of cost accounting. For example in hotels it starts with the units for sale as seen in the revenue metric REVPAR (revenue per available room). While there are other important metrics beyond that one in that particular industry, the available room is foundational since that is the essence of what a hotel is selling.*

In defining the relevant units we must understand if the units are variable or fixed, if the units are fully or partially or not at all under our control, how the units behave independent of cost (think of seasonality, etc.), when certain costs (or revenues) do and do not apply to various units. In the last case consider a restaurant where the cost applied per table seat available might be separated from the cost applied per bar seat available even though we would still want to look at them in totality. Hence a mythical unit might be created to synthetically mimic the real units on an aggregate basis--e.g., cost per customer spot available.

Not complicated enough? Add in a dimension of time. Open a restaurant an hour longer each night--do your relevant units change? Cost certainly will. Depends on how you define units given the objective you're trying to actually measure.

From cost we next need to know revenue from which point we can understand profit. Allow me to illustrate using a personal anecdote from my time as a financial analyst at a newspaper.

One of the reasons I was hired was to understand the cost and revenue drivers as profit margins had begun shrinking in the industry. I like to say that a fat profit margin hides a lot of bad decisions. The newspaper industry was no exception. Quite a few things were able to be tried that once a thorough analysis was conducted turned out to not be as successful as expected or believed to be. This isn't a bad indictment per se. Success in business is built on a mountain of well-placed failures.

Of all the things I was asked to do, I was never explicitly asked to determine the specific attribution of the company's profits--meaning what lines of business were profitable. Yet this seemed a natural thing to want to know. In fact it fascinated me. To everyone else it was obvious or uninteresting. They simply "knew" what was profitable. Profits were so big, heck, everything was profitable, right? That was intuitive to some but not to me. My intuition was the opposite--I knew that it would be highly unusual for everything that went into a bundled product to be profitable in the sense of direct attribution.

There seemed to be two biases at work: a fear of knowing the answer (what if my area isn't profitable?) and a lack of critical thinking (look at how much revenue this generates/this is an essential part of the business; it must be profitable).

Once I achieved a strong understanding of the company's cost, it became apparent that everything simply could not be profitable. There were vast differences in revenue by various business lines but very little differences in properly allocated costs. Applying revenue minus cost (i.e., profit) business line by business line would "use up" the profit before all the areas were covered. Before mentioning the areas that were profitable, a caveat is needed. The newspaper was a bundled product meaning everyone got the main section, the sports section, the monthly special sections, the inserts, the classifieds, etc. A point of near religious dogma in the industry was how vital nearly all of these components were to a successful bundle. So I was both risking heresy as well as producing an analysis that the very cost-conscious management team might misinterpret much to its own demise. Loss leaders is a very real and healthy business practice as is cross subsidization. But these concepts can also be co-opted to excuse bad mistakes were money is lost for no actual indirect gain.

Everything wasn't profitable. Out of nearly a hundred different product lines and sublines, only four areas accounted for 100% of the profit of the business: preprint inserts, national ROP ads (when a company like American Airlines ran a full-page newsprint ad), color ink (a big upsale item), and employment ads in the classified section. This meant all the other ads in the main, sports, business, and other newsprint sections including special sections were losing money. All the rest of the classified section outside of employment ads were losing money--ad areas like traditional for-sale listings, automotive ads, real estate ads, etc. The circulation revenue was not covering costs. Subscribers were not paying enough to cover the cost of delivery much less any content production.

The entirety of this analysis was not a complete surprise to the seasoned people at the helm of the paper, but the details were revealing and eye-opening. To repeat and be fair, this did not mean that people like the guys selling automotive ads weren't adding value--they certainly were. But what they were adding was content value much like the guys writing the sports columns. The upshot was that a limited decision-making mantra could have been "How will it help increase preprints, national ROP, color, or employment ads?" If the answer was "it wouldn't", the right decision would be to reject the proposal.

Knowing cost is not easy; so a good deal of respect is owed the business people of the world who work hard to master it. This might start with the cost accountants I was slighting in the prior post, and it certainly ends with all those entrepreneurs, business middle managers, and captains of industry toiling away so cost is never unknown.

*There are always exceptions. Some hotels are selling experiences outside of the room itself. The room might not correspond tightly to variable costs or to revenue. However, usually even when there are multiple lines of business (think Las Vegas hotels), these still are broken down per available room as it corresponds to cost and revenue as tightly as any other unit.

Sunday, May 1, 2022

The Accountants Can't Make You Rich

In business cost per unit may be the ultimate metric. Accountants focus on in decreasing the numerator. Marketers focus on increasing the denominator.

It is important to remember, though, that cost containment is not a growth strategy. Accountants almost never remember this. However, it is a necessary but not sufficient condition for long-term success. This is true of economies, firms, and individuals. In a future post I will explore this giving the importance of the metric its due.

You can't grow your wealth by harvesting investment losses--you can't just "write it off" after all. Reducing unnecessary costs is an important part of sustaining a firm, but it is not a complete recipe of a succeeding firm. This is why so many mergers and acquisitions fail to add value. Cost reductions through economies of scale are generally very difficult to realize, and even when they are realized, they are often temporary. Ultimately, successful mergers come down to realizing synergies for new growth without cost exploding. Compounding the problem of pulling off a successful merger (one that justifies the purchase price of the target being acquired) is that the hoped-for synergies prove in many cases to be imaginary and as often unforeseen at the outset--more luck than skill.

Looked at from a broader view, a society with high savings and poor investment will be an impoverished people who are soon forgotten. To be clear the alternative isn't simply live for today, but at least those of the Bacchanalia had a good time while it lasted. The miser who squirrels away his every penny under the mattress has nothing to show but a desire for yesterday's purchasing power.

The cost reduction impetus gets maximized in a recessionary environment. Firms and individuals tend to look inward in times of economic stress thinking more and more about how to voluntarily shrink to avoid forced shrinking. This can be both helpful and healthy. Yet taken to extreme, which can come quite easily, this becomes a self-fulfilling feedback loop.

The cutbacks one should make are reductions in consumption. This is a lot easier at the individual and family level than at the firm level. Firms shouldn't have "consumption" per se. To the degree they do this is simply excess that should be trimmed away in any environment--easier said than done of course. Investment choices may and likely should change given changes to near-term outlooks. At the same time the risk of overcorrection is very great.

An asset allocation should be largely immune to changes in the investment near term. The investors "going to cash", "moving to the sidelines", and selling out otherwise in times of stress in the financial markets are almost always making critical mistakes. Sometimes those mistakes are permanently devastating.

Back to the general concept of keeping the accounting department happy, accountants usually aren't thinking in terms of calculus--only calculations. What I mean by that is they aren't looking at rates of change and the signs on the derivatives. Lest we degrade them unnecessary, the marketing department's version of calculations can amount to astrology mixed with magical wishes. At least the accountants are doing real math.

Those exaggerations aside keeping an eye on cost is essential. Focusing entirely on cost is deadly.

Saturday, April 30, 2022

Choose: Stocks and Bonds or Bitcoin and Cash

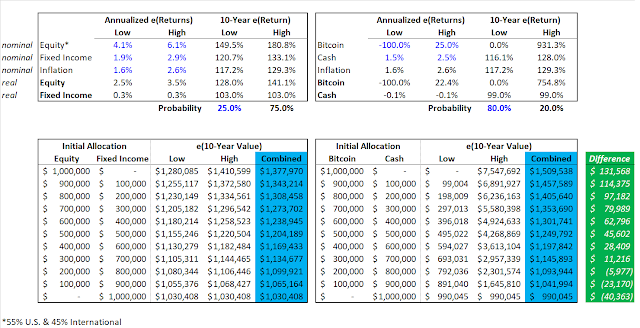

Over lunch this past week an interesting hypothetical was posed. Suppose you were offered one of the following, which would you choose:

- One million dollars in some initial combination of your choosing between stocks and bonds (fully-indexed, total market coverage), or

- One million dollars in some initial combination of your choosing between Bitcoin and cash (U.S. dollars).

You will be forced to lock it in for 10 years with no changes to it or any ability to borrow against it. After the 10-year period is up, it is yours free and clear (no taxes either at that point).

Without too much thinking or much hesitation, I chose Bitcoin and cash in a 50/50 combination. My wiser colleagues said with as much or more conviction stocks and bonds--I don't recall their combinations if they stated them. Since I am the investment guy, this raised eyebrows. Maybe I'm just also the gambler. To be sure I caveated my decision with the disclaimer that I might change my mind (my guess was low conviction). To be fair the others did similarly but with perhaps a bit less hesitation (somewhat higher conviction).

In general I would assume that all four of us in this conversation are of very similar financial standing adjusted for our ages (there is about a 30-year spread from youngest to oldest). There is not a right or wrong answer on this question--at least not without a lot more information about each chooser including several underlying assumptions (risk tolerance, liquidity needs, expectations about each person's future goals and paths of life, etc.). I don't wish to get into speculation about that here nor try to evaluate the soundness of any starting position.

What I am interested in is exploring further how we might frame such a tradeoff. One additional outcome from this exercise is thinking about what assumptions one would make about critical variables and the implications of those assumptions.

Some people would very appropriately, for themselves, choose an allocation of 100% cash. We could argue about that, but again only by digging deeper into their goals and risk tolerance among other things. "Hey, I'll take free money and I want to know it will be basically there for me at the end of the rainbow (inflation be dammed!)." That is potentially a sensible position, but we could write a book (many books have been written) about what extreme conditions must be in place for that to be rational. Geez, I better stop now or that will be this post . . .

So let's just assume we are debating only the question of which outcome has the best highest expected value after 10 years. I strike "best" because that implies more than just the math problem I want to explore.

We need just a few inputs:

- expected returns of stocks, bonds, Bitcoin, and cash (I am assuming we can get some yield on cash rather than thinking of it as money under the mattress.)

- expected inflation (We are going to look at values in real terms so we don't let the cash option appear better than it actually is--a likely net loser to inflation.)

- probability of various outcomes (Using a range of expected returns we need to know how likely we think those are. The range is really only important for Bitcoin given its unknown future.)

I am going to use Vanguard's capital market assumptions (CMA) for expected returns of stocks, bonds, and cash as well as inflation. To make these always updating predictions evergreen in this post and because these are publicly available information as linked above, I will also post a picture of these below. Please do see Vanguard's website for more information including appropriate disclaimers.

I am going to totally make up the expected returns for Bitcoin because 1) my guess is as good as yours and 2) the devil is in the probability and the relative outcome versus the others--my accuracy is nearly immaterial if I am in the ballpark.

Before you dismiss any of this upon glancing at the inflation prediction (range 1.6% - 2.6%), understand that these are 10-year predictions. I hope they are right given what this implies going forward given currently very high inflation rates, but it can easily be the case even with some persistence of current inflation (8% for a year (not that bad yet) plus 5% for a year plus 8 years at 1.6% would land us at the high range).

Note that I am looking at true total market coverage in stocks (U.S. and all international), thus I will combine the growth rates below in the proportion 55/45 U.S./Int'l. Note also that I am only using U.S. bonds in the model. I generally like some international bonds, but I will make this limiting assumption. Regardless, U.S. versus Int'l bond returns are pretty close as you can see in the details below and at the link.

Enough of that already, let's model this thing.

Here is version 1:

But just before that, let me explain why I don't think we need to worry about the mixing and matching between individual high and low estimates (e.g., stocks grow at 6.1% while bonds only grow at 1.9% or stocks and bonds are high but Bitcoin and cash are low, etc.). Assets tend to be positively correlated over longer and longer timeframes. Even though stocks and bonds enjoy some degree of poor correlation, these fade away over time as what is good for stocks (a productive, growing economy) is also good for bonds. Likewise, a world that has Bitcoin doing well probably has stocks doing well, and a world where inflation is low, stock and bond returns are also probably low. Regardless, the heart of the debate isn't going to be impacted by these details.

Here is version 2:

Ouch! Even though I made the low-high range for stocks and bonds 50/50, the move to make low to high outcomes 95/5 for Bitcoin destroys that option. But if that is really more like the future likelihood of the outcome range for Bitcoin, perhaps stronger return possibilities on the high end are as well. So . . .

Here is version 3:

I greatly increased the growth rate for Bitcoin using 38.6% annual growth. This isn't a randomly chosen number. This would correspond to a Bitcoin price of approximately $1,000,000, which some roughly project as a possible destination (who knows?). Regardless, stocks and bonds still look better. So let's do just two more for the sake of good order . . .

Here is version 4:

Finally, here is version 5:

So, allowing for a Bitcoin future in any future (low end is 10% annual decline in value) gives us a fairly strong case for my gamble on some combination of Bitcoin and cash.

Having gone through this process would I now change my mind? I will stick with 50/50 Bitcoin and cash. But that strongly suggests a question: how can I justify that choice given that I don't have an existing portfolio that looks anything like that. I am personally overwhelmingly "boring" with an almost all-stock portfolio with just a bit of crypto sprinkled in.

At the risk of a slight digression into the post I keep promising this will not be, allow me to defend my rationality. This hypothetical is a forced gamble. My retirement investments are different in that regard. Those I can and do change periodically including both allocation as well as contribution. I get to guide those and adjust them. The hypothetical gift invested is a Ron Popeil "set it and forget it". Part of why I cannot invest more in Bitcoin (aside from it wisely not being a 401(k) option (looking right at you, Fidelity)) is that I likely cannot tolerate the variance. If I can get in and get out of it, I am as more likely to make the wrong in/out moves as the right ones. And that is before the tax-drag effect.

Besides that, my investment reality is the retirement assets I actually do have. This hypothetical is a lottery ticket idea. If I win the lottery, my reality materially would change. I could afford more and different risk. In this sense and surprisingly, if the hypothetical was $10,000 in stocks and bonds versus Bitcoin and cash, the rational decision for me might have been stocks and bonds! Whereas the typical person would say, "that is too little to worry about the risk, let it ride!", I would counter, "I can't afford to take the the riskiness of Bitcoin at that magnitude ($10,000)." Along this one dimension, I would be right.

I want exposure to big upsides. Unfortunately, these are difficult to find and doubly difficult to stick with. In a sense this thought experiment has revealed some of my own limitations on putting my money where my mind and heart and mouth are.

-----

Sunday, April 24, 2022

If you've ever handled a penny, the government's got your DNA.

File this under: Wanted: new conspiracy theories—all ours came true.

When DNA testing and genomic profiling was first rolling out as a mass-market product, I remember hearing people objecting to it saying things like, "I don’t want them to have my DNA".

These worries were summarily dismissed by science-supporting elites as paranoia on the part of anti-science or antisocial bumpkins.

It turns out an ounce of caution here was warranted.

And then COVID happened . . .

And now 23andMe has come full circle:

Wojcicki says that’s just not going to happen. “We’re not evil,” she says. “Our brand is being direct-to-consumer and affordable.” For the time being she’s focused on the long, painful process of drug development. She’d like to think she’s earned some trust, but she hasn’t come this far on faith.

Caution continues to be warranted by at least some elites (Macron refuses Russian COVID test), and I don't blame them--be sure to click through to the Atlantic story about the lengths to which the White House goes to protect the president's DNA.

I understand Macron and the White House taking extreme precautions in this area. I also do not think it is highly likely that anything bad would come of genetic data gathering in general. In fact I tend to be supportive of the secondary (or ulterior) uses that genetic data could provide--provided there are adequate disclosures on the front end and transparency throughout the process. Trust but verify is the right approach.

The level of trust is inversely proportional to the extent to which people's fears get realized even if they are only partially realized. In other words the level of trust is directly proportional to the degree of proven trustworthiness.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)